Josiah Enyart remembers getting the

memo. For the fall semester of 2021,

months after the COVID-19 pandemic

had fizzled out and most people had returned to life as usual, the public school

district where he taught in Kansas was

still going to mandate face masks for

students and teachers.

Josiah Enyart remembers getting the

memo. For the fall semester of 2021,

months after the COVID-19 pandemic

had fizzled out and most people had returned to life as usual, the public school

district where he taught in Kansas was

still going to mandate face masks for

students and teachers.

Enyart had been struggling in his job as a teacher in Shawnee Mission School District for months, frustrated by leftist policies and critical race theory encroachment that sacrificed student learning upon the altar of liberal ideology. The mask mandate was more than he could take.

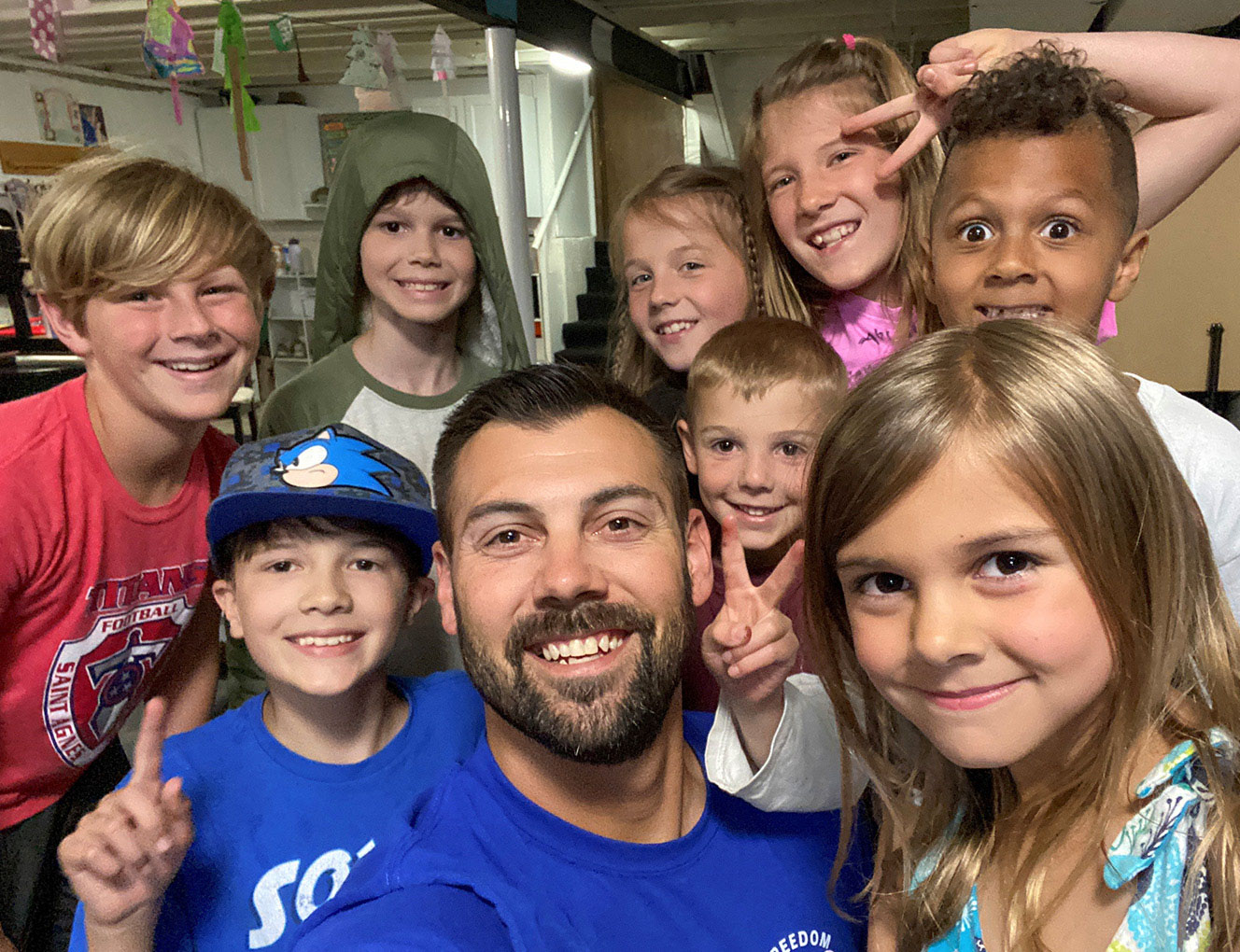

Enyart resigned from his position, effective immediately, and began a learning academy that has since grown to almost 50 students.

"We're going to teach your kid academics," Enyart says. "We're going to teach them math, reading, science, social studies. We're not going to hide from the truth. And then we're going to teach them character traits of successful people — like resolution, responsibility, compassion, temperance, industry, humility, tranquility, empathy, sincerity and moderation."

Enyart's efforts so far have been hugely successful, both in quantity and in quality.

"Most of the kids are making a year and a half to two years of gains in a year," he says.

A native of Shawnee, Kansas, Enyart became a Christian as a teenager. He played baseball in high school and knew that he wanted to continue the sport in college.

"I didn't really know what I wanted to go to school for as long as I could play baseball and find a good church," he says.

He spent two years at a community college in Kansas before Union University offered him the opportunity to be a Bulldog. His time at Union proved to be formative in his life, with classes that he said prepared him not just for a career, but for life.

"It was beautiful," Enyart says. "The people were great. The professors all seemed to really like what they were doing and be effective at it."

A 2009 graduate with a Bachelor of Science degree, Enyart says he was especially grateful for required Old Testament and New Testament survey classes that instilled in him a knowledge of the Bible and a desire to study it deeply.

"I still have my notebooks from those classes," he says.

He met his wife Bethany at Union, and after graduating they moved back to Enyart's home state of Kansas, where each of them found jobs. Enyart's first position was as lead teacher at a modified Montessori school, where he also coached, drove the bus, functioned as the principal and cleaned the facility. His long-term goal was to teach and coach at his high school alma mater, Shawnee Mission Northwest — a goal that became closer to reality when the school district hired him to teach third grade at Comanche Elementary School in Overland Park.

Everything went well for Enyart for

several years at Comanche, even in a difficult environment.

Everything went well for Enyart for

several years at Comanche, even in a difficult environment.

"We had the highest mobility rate, the highest minority rate, the highest number of kids on free or reduced lunch," he says. "Our population was very, very challenging in the sense that they didn't have resources or as many positive influences and ways out of the poverty system."

Still, his principal was effective. Teachers were committed. Students were learning. Enyart moved from third grade up to sixth grade and felt like he was contributing to his students' welfare.

But then Enyart began noticing cracks that eroded the strong foundation the school had built. One year, with a new principal in place, the school district mandated a training program called "Deep Equity" by Corwin — a "diversity, equity and inclusion" initiative that pushed "just how privileged we were as white people," Enyart says.

"Assuming, based on my skin color, that I am this certain person is to me the definition of racism that made no sense to me whatsoever."

Other questionable decisions from the school district followed — technology mandates that cost a fortune and did little to improve student learning, changes in curriculum and teaching methods that Enyart says were detrimental to students.

"Every decision they made, made everything worse," he says. "We continued to do these DEI trainings that taught us how terrible we were as white people, how impossible it is for anyone to succeed if they're not white. Just all these terrible negative messages that did not at all speak truth, speak success, bring joy, bring confidence in education, and it just started to crumble."

Upon his resignation, the district charged him a $1,000 "liquidation fee" for not providing them with ample notice before the start of the fall semester.

Enyart protested the fee, but the school board remained unmoved. By this time, his story had started to attract media attention, and some of Enyart's supporters started a GoFundMe account to raise the money the district was charging him.

That effort garnered even more media coverage. The Daily Wire picked up Enyart's story, and he was interviewed on Fox and Friends. By the time the fundraising effort stopped, more than $22,000 had been contributed to Enyart's cause.

He used the extra money to launch Freedom Learning Academy and to remodel his basement for classroom space.The initiative started when Enyart's cousin asked him to teach her son and three other kids, but the media attention sparked even more interest from parents who didn't want their children in public schools anymore.

From 15 students that first semester,

the enrollment has increased to 55.

From 15 students that first semester,

the enrollment has increased to 55.

"We are what we call a micro school. It's a non-accredited private school, which is the fancy term for home school in Kansas," Enyart says. "But in Kansas, you can, as a parent, choose who educates your kids and choose where your kids go to school."

Since the academy's launch, Enyart has hired three other full-time teachers, in addition to himself. They instruct kids in kindergarten through eighth grade, with ninth grade being added in the fall of 2025. He also has five part-time teachers. The school quickly outgrew Enyart's basement and now meets at a local church building.

"The goal of the school was to provide a safe school environment where the kids actually have a strong academic regimen that promotes their academic growth, but also development of their character," Enyart says.

Though the school is not officially a "Christian" school, Enyart says it certainly is based upon Christian themes and values. And it has found a niche in Kansas for concerned parents who want more for their kids than what the public education system there provides.

"As a school, I want to prepare the kids to be capable of exceeding the expectations of the state," Enyart wrote in a blog post on his school's website. "I want to prepare them to have the skills they need academically and socially to be successful by the time they are ready to finish high school. I want to prepare the kids by instilling an intrinsic motivation to work hard and follow their dreams."

That desire, in part, came from his time at Union.

"College is for acquiring the knowledge you need to be successful in a given field as well as learning how to be an adult and manage your own life," Enyart says. "I got all of that and more from Union."